Gamasutra recently posted an interview with Ken Levine on the nature of storytelling in video games. His most poignant comment centered around storytelling’s unique position in the industry:

Every time I write a game, I think I learn how to write less — how to get an idea across with less text. How to rely on the visual space, whatever the visual elements you have in the world, or in the characters. People saying stuff is the last resort in a video game, especially if it’s going to constrain the player from acting. You know, I want the player to be active. Active, active, active. So you just really learn, you sort of sharpen your toolset each time out. I try to get across the same amount of ideas, but I try to use less text to get that idea across. I don’t know if I’ll succeed, but I’m trying.

I’m about to finish Bioshock, and I can attest to Levine’s storytelling genius. One of my favorite scenes in Bioshock occurs near the middle of the game when you visit an area controlled by an egocentric artist named Sander Cohen. Cohen’s writing and voice acting are both top notch, but it’s the environmental storytelling and design decision that really bring his story to life.

The player’s first encounter with Cohen is a complete surprise. While walking to a bathysphere that will take the player to the next area, the familiar voice that is constantly chirping in the player’s ear suddenly goes silent. The room then transforms into a hauntingly beautiful room of purple and plaster, and the player hears Cohen’s invitation to join him in Fort Frolic. Clearly, Cohen is in control now.

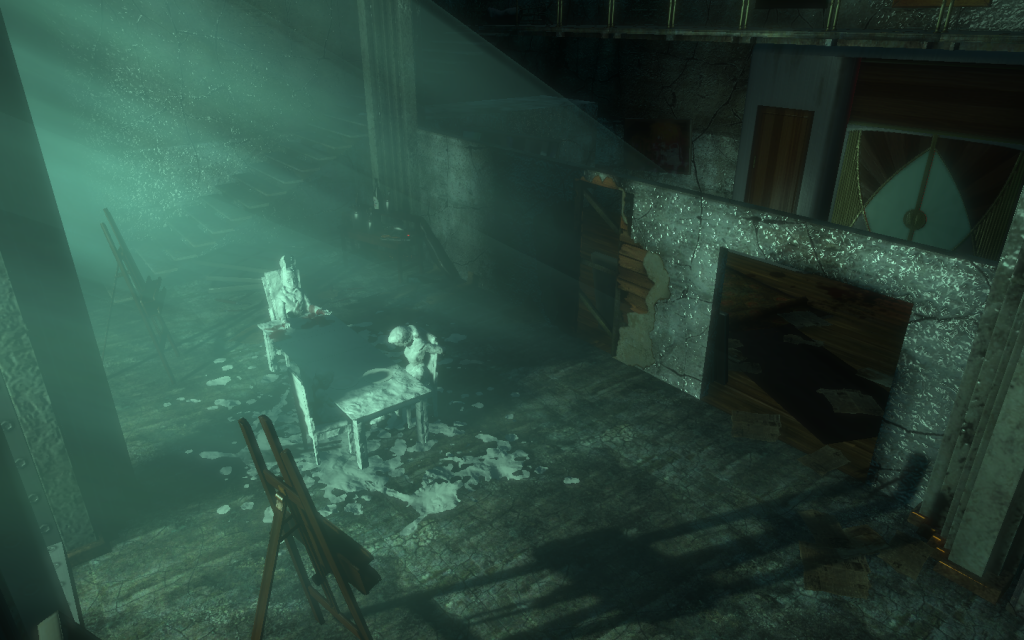

Fort Frolic is saturated with bright lights, extravagant stages, and seemingly all the trappings of the artistic world. But the player later finds Cohen’s room and walks in to see this:

The room is a stark contrast to the rest of the Fort Frolic flamboyant environments. It is dark, cold, and adorned only with a few sparse paintings and the plaster-covered corpses of splicers. So what does this say about Cohen? Well, clearly he is an unbalanced and dangerous man. But digging beyond suggests that Cohen is a man facing completely outward. His obsession with creating outward beauty has left his most inner core, typified by his room, bare and dark.

Levine and his team didn’t use blocks of text to convey this about Cohen–they used a room. They used the environment. They ensured that players could explore the underlying story and discover the world completely at their own leisure.

Examples like this are too numerous to begin mentioning. But they all have one thing in common: they communicate a story with few or no words. This kind of storytelling is essential to games because it harnesses the medium’s inherent interactivity. Players can see as much or as little as they want, and in this way, they make the story their own.

I'm a game designer with years of industry experience and a master's degree in design who's worked on AAA games, indie darlings, and free-to-play products.I love using my design and scripting experience to create awesome products, especially when it means working alongside a passionate dev team.Take a look around at some of my work, and please don't hesitate to reach out if you have any questions or opportunities!

I'm a game designer with years of industry experience and a master's degree in design who's worked on AAA games, indie darlings, and free-to-play products.I love using my design and scripting experience to create awesome products, especially when it means working alongside a passionate dev team.Take a look around at some of my work, and please don't hesitate to reach out if you have any questions or opportunities!